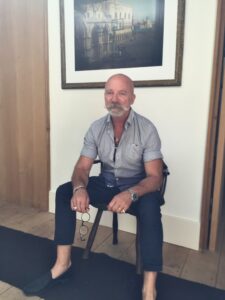

An interview with a prestigious name in the design sector: the internationally known architect, product and interior designer, professor, founder of the avant-garde NATO group in the 1980’s, Father of Narrative Architecture, visionary of Body Buildings and CityScapes, Creator of the Ecstacity, Advocate of Art in Architecture, and so much more: Nigel Coates.

Coates has challenged and questioned the meanings of the role of architecture and design, the structural identity of a city, and a home, while concurrently bringing forth an artful manner that introduces a new way to relate and perceive the physical entities in our habitat. He is a creative chameleon with a progressive and experimental future-driven attitude; his original narratives have translated into many buildings, interiors, and exhibitions around the world.

The sense of discovery is a common denominator within all fields where Coates operates; Design & Architecture works in an endless spiraling flow of ideas with each new idea containing the germ of the next one, whilst every project both originates and excavates.

In this Interview, Nigel Coates shares his thoughts and experiences spanning from challenging the practice of architecture and the importance of a disciplinary crossover as a reflection of how we live to the notion of change within our fast-changing era. From the relevance of Ectacity’s cyber-punk vision in our lives to how economic hardship can lead to invention, and the evolution of the “digital ubiquity” accompanied by the creative attempt to make things out of it. From the recurrent references in his work when it comes to a partnership between our own bodies and the environments that we create to accommodate them to our egocentric “me” culture. From the death of the era of applied branded design language to the meaning of a flexible, inquisitive home — a space open to performance as a West End theatre. From the cost of beauty to a mix of education methods and the importance of students engaging with social evolution to broaden their practical, intellectual, and emotional mindset versus sticking to a tick-box design process…

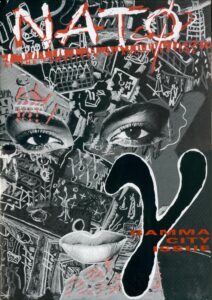

NATØ Cover, AA Publications, 1985

You have challenged the practice of architecture – overlapping it with fashion, design, and the history of ideas. How much more relevant is this disciplinary crossover today in general?

In my mind, a crossover is more relevant than ever, because that’s how we live our lives. In the digital world, we multi-platform all the time. Messages arrive on so many different apps that just finding them can be a problem. I understand the appeal of thinking about architecture as a practice apart; the rationalist position is about the constancy and absolute nature of type and typology. But how we synthesize constantly is more relevant: any journey moving through a city involves observing signs, traffic, people, and buildings. We’re experiencing an interactive condition, so it follows that architecture should aggregate experiences rather than partition itself off. I’m not suggesting an architect should know how to cut a garment on the bias, but at least know what that means. In the 80s, I was inspired by fashion because it was fast and responsive; a collection could be a manifesto with broad cultural implications, like say Vivienne Westwood’s Pirate collection. It helped me become a pirate architect!

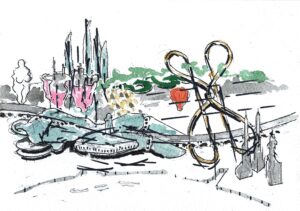

© Nigel Coates, 2020

The MDFF World Tour Athens 2020 carries the title “Lights On: Projecting Our Contemporary Future.” The program invites us to reflect on how we communicate with one another, with our cities, and, ultimately with ourselves. Moreover, it addresses the relationship between project and innovation, memory and future, similarities, and diversities. How has your design approach and clientele changed over the years? How comfortable are you with change on a personal level?

Again synthesis is the answer. I try to live in the moment, simultaneously with hindsight and an eye on the future. I look for dynamic models to ‘traject’ socio-cultural phenomena towards the near future. With all this Covid-19 stuff, we’re in an extreme moment that will have a profound effect on cities and our entire way of life. Power-hungry governments will use it to facilitate their impending power-grab, but those of us that cherish openness and democracy will fight to create new circumstances that underline freedom. In terms of clients, in the early part of my career, they wanted show stoppers to outshine their rivals. That was especially true in Japan, news of which back home reinforced my reputation as a trouble-maker. As we grow older, so do our clients: now, they aren’t looking for iconoclasm, and that suits me fine. My work now is cleaner, less cluttered, but with the same sense of discovery as always.

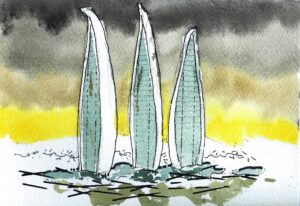

© Nigel Coates, Body Zone, London, 2010.

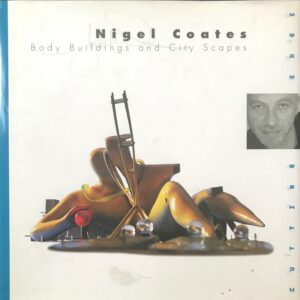

© Nigel Coates, Jonathan Glancey, Body Buildings and City Scapes, Thames & Hudson, 1999

In your work, what is the cost of beauty, and what’s the value of beauty? How has it changed (if it has) over the years?

That’s an interesting angle — the cost of beauty! In some ways, it’s always been there, depending on who and how you look. At the other extreme, it can be used as an instrument of power, and therefore be monetised. But beauty today is not so much visual as perceptual in the wider sense. I’m an advocate of art in architecture; there is a mathematical beauty too: in the rhythm of a colonnade; or the golden section. Music is often beautiful, and you hear it rather than see it. Stories create beauty with the dimension of time, taking you on a journey that twists and turns, against which space is just a background. As for my own work, I’ve always looked for ways to express beauty, but it has taken so many forms over the years. Pretty much everything I do has a classical underbelly that has been subjected to the mincer of experience. My efforts are most effective when they catch you, the viewer, off guard. Beauty could capture visual perfection – the classical ideal – but it’s more likely to reveal vulnerability, sincerity, a battle against the odds, or unearth some primordial sentiment. I have always appreciated some people’s struggle to express beauty, the motivation to emulate, like the local craftsman who tries to emulate something stylish he’s seen by chance and, during the crafting process of making, gets it slightly wrong. On the other hand, a thing works when it achieves autonomy and no longer needs me to prop it up.

© Nigel Coates, Picaresque, ‘Kama, Sex and Design’, Triennale di Milano, 2012

© Nigel Coates, Picaresque, ‘Kama, Sex and Design’, Triennale di Milano, 2012

During the lockdown, you published on socials the notion of the lockdown living through your fictional project “House for a Whistleblower.” Tell us more about the message behind it.

I did this project a few years ago for a magazine called TAR. The idea was to explore a closed domestic world, and how it could sustain the sanity of the inhabitant who, in my fictional work, was Edward Snowden, the whistleblower who passed a vast cache of covert documents to Wikileaks. Under threat of arrest by the US government, he was granted asylum by President Putin in Moscow. In his closed-off world, he would need to be entertained and informed by the landscape of the interior space. Beyond my admiration for Snowden, his imagined lockdown home would be a great way of showing off my design work – the table, chairs, lamps, and bed – that would merit a privileged environment in which they could be surveilled up to the eyeballs. The project was conceived and executed like a fashion story or a short film, with a model standing in for my hero, a built set, and a photo session by filmmaker friend John Maybury. With Covid-19, it is the perfect moment to bring the project back out into the open.

© Nigel Coates, Hypnerotosphere, Biennale di Venezia, 2008

When it comes to the city as a living organism with its own narratives, what would/could be a “new light” to shed upon your research projects such as “Ecstacity”?

“Ecstacity’s” cyber-punk vision has actually come about. We’ve been living it. Since I first explored the idea in the early 1990s, the project has unfolded with its two main themes, having become consistently relevant. The first is the ideal of a city with an exaggerated cultural mix: in the project, a blend of seven cities characterises the globalised city we are all familiar with. The second principle is embracing pleasure as a component of urban life, and how an architect or city planner can incorporate it into their understanding of how cities work organically. Alongside connectivity and the narrative experience of work and leisure, these touchstones are as valid as they ever were, apart from the exceptionalism of the megacity. The rewards of pleasure won’t be confined to the city. You’ll be able to hunt it out anywhere and everywhere. Instead of “Ecstacity,” I should be talking about “Ecstaworld.”

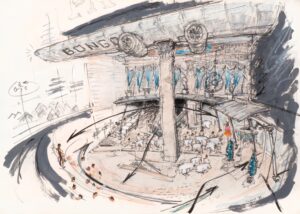

© Nigel Coates, Caffè Bongo, Tokyo, 1988. Graphite, acrylic and oil pastel on paper, 420 × 590 mm

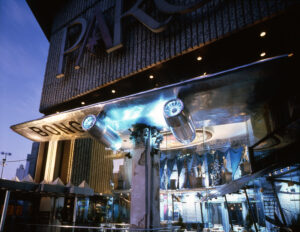

© Nigel Coates, Caffe Bongo, Interior, Tokyo, 1986

© Nigel Coates, Caffe Bongo, Interior, Tokyo, 1986

What is the biggest challenge for architects and designers presently? Is this a fertile moment for the creative community to find solutions even to a problem that is not clear yet?

If you’re an architect in practice, the biggest challenge will be staying in business. But creative minds never stop, and in some ways, economic hardship actually raises the bar. I predict there’ll be a lot of invention around the design of open space, parks, public squares, and how these can extend, frond-like, into the countryside. Assuming that this coronavirus will be with us for a long time to come, we need to look at the whole ecology of society, including the electric vehicles and techno-clothing that will help keep us safe.

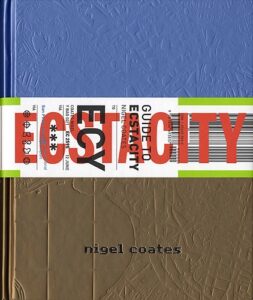

© Nigel Coates, Guide to Ecstacity, Laurence King, London, 2003

Nothing that occurred can be erased. Even if we carry no physical signs of having lived a given situation, that specific situation is still imprinted in our emotional and mental DNA. What is this “Digital Ubiquity,” and the disrupted “co-existence” between our cognitive senses and our digital ones?

What you call this “Digital Ubiquity” is certainly with us, but as it advances, so do the attempts at making things without it. Look at the success of cooking programmes; apparently, everyone wants to be a chef. While the smartphone has genuinely changed our lives, I’m not one to jump on every gimmick presented at the CES show in Las Vegas. To get a feel of how these two phenomena can coexist, you have to study children. They don’t really distinguish between the two and are busy learning at a rate never experienced by my generation. Once again, the biggest problem is the erosion of personal freedom.

© Nigel Coates, Ecstacity, AA Publications, 1992

You see a high value in risk-taking and experimentation. Could you share with us some of the projects that you plan to shift your focus towards? Are the projects defined by a revisiting, rethinking approach? Or projects that got disrupted due to the crisis and that you shall return to and continue?

I’ve continued to work throughout the crisis, switching between several book projects and a new design initiative for a furniture company in Vietnam. Every piece I design is meant to work for the imminent future, be feasible to make, affordable and desirable enough to sell. Essentially, I’m the same designer as I always was, with recurrent references and methods.Some themes make guest appearances. I go on about the body and how it needs mirroring in our surroundings. Somehow I’ve brought the body into almost everything I’ve done. There’s also a zoomorphic undercurrent; many of my chairs have animalish legs that are about to spring into action.

© Nigel Coates, Narrative Architecture, Wiley, 2012

Is this also a moment for an “osmosis” between the I and We space?

Never throughout history have we experienced a more acute threat to our culture than we do today. In the past, there have been many me cultures at the top – the Neros and the Louises of yesteryear. The me dimension has grown incrementally with social media to the point that now, consumer culture equates with the right to me. But there are also many I’s. There is an intimate side to the me, or what Freud called the Id: the intimate, instinctual self, moderated (we hope) by the moralising psyche: the super-ego. Egocentric me culture has grown at the expense of the other two — the id and the super-ego. That said, young architects are passionate about contributing to a better world, as witnessed in endless school projects highlighting the homeless, refugees, global warming. Tables turn later on: when a rich client comes along, this leads to compromise.

© Nigel Coates, Mixtacity, ‘Global Cities’, Tate Modern, 2007

Based on the open-source collaboration between different fields of different scales we witnessed during the pandemic, if we were to revisit the archistar notion, what could be some newly generated views? Can we reorder pre-set “hierarchies”?

The very idea of the archistar seems jaded. It was always about the architect as a brand, and only a few achieved that status. In the light of the diminishing of power of the architect, archistars hang on to control with grim determination. You may have been hired on the basis of your press cache rather than your ability. There are many ways in which an architect can disappoint, by proposing a stock solution, or an ‘arrogant’ response that’s out of scale or place. My skepticism extends to the lack of collaboration in the output of many an archistar. The idea of a branded design language being applied to building, furniture, and every fitting, seems as dead as the gaslight. Achieving the status of the brand seems counterproductive.

© Nigel Coates, Mixtacity, ‘Global Cities’, Prada Skirts, Tate Modern, 2007

© Nigel Coates, Mixtacity, ‘Global Cities’, Mixtacity Central, Tate Modern, 2007

In your opinion, which are some current architectural paradigms that are valid enough to “stay,” and which are some that need to be revisited or even “abandoned”?

I’m not really interested in a league table of styles, but post-modernism seems to be on the rise, and parametricism is on the wane. Personally, I’m sick of shedchitecture; how often do we see half-baked glass and plywood house extensions being promoted as cunning solutions? I’d never dismiss poor or recycled materials being co-opted into a clever mindset. My hope is that repurposing with flair will not only persist but get better and more courageous. And when it comes to new build, we need strategies that emulate the dialogue between old and new, with distinct temporal conditions that evidence the solid frame and the more temporary scenery.

© Nigel Coates, Voxtacity from the air, Vauxhall Gardens, London 2017

© Nigel Coates, Voxtacity, Canoe Heights, Vauxhall Gardens, London 2017

© Nigel Coates, Voxtacity, Entrance Zone, Vauxhall Gardens, London 2017

What does home mean to you? Are the interiors of our personal space an expression of a closed world where aesthetic, functional, interpersonal, and even emotional performance need to “reside” harmoniously?

The performance of the interior is one of my pet subjects, which I know isn’t the interpretation of the word “performance” you meant. But indulge me please. We may think of the home as exempt from performance, but in reality, it is as open to performance as a West End theatre. It’s just that the performance is at the micro-scale and intended for the resident in question, and their family and friends. Firstly, the home has to be comfortable and workable but needs to be responsive too. The TV and computer bring information and entertainment into the home, but the way space is designed should be a factor in both. Spaces and furniture together define the landscape for everyday life, and should constantly talk back to you. The home should ask questions. Why not move to eat here? Try sleeping here? Read a book here? My perfect home is subtly changing all the time, according to the weather, my mood, and who’s there with me. The “House for a Whistleblower” is just such an exercise, a bit like a caravan in which, for reasons of space, every element doubles its function. But having that bit more space can accommodate a variety of intersecting scenarios that can be re-enacted according to the circumstances.

© Nigel Coates, Paracastello, Fuorisalone Milano, 2015

You spoke about the exportation of our notion of the body to architecture. How would you explain the interconnection between body action and space? How could this body metaphor of architecture assist us when re-articulating the way we evaluate buildings?

I’m not talking about the ghost in the machine, but the benign partnership between our own bodies and the environments we create to accommodate them. Every building contains the trace of the body – in its planning, in its doorways and windows. But going further, if we prioritise it, the body can drive how space is expressed. This is why I’m interested in certain kinds of buildings where the body is key, like nightclubs or stadia. Conversely, the body can affect how you conceptualise space – by imagining the experience of moving through it as an integral part of the design process. Design is like directing a movie: it needs a protagonist to tell a story. And that’s why there’s an actor in the Whistleblower project.

© Nigel Coates, House for a Whistleblower

The students you interact with and have associated with — as head of the Academic Court at the London School of Architecture and Professor of Architecture at the Royal College of Art — belong to the generations that will probably have to face today’s challenges, even more than us. What are some new approaches in teaching architecture, and how can education better prepare the architects of tomorrow to better understand social evolution and respond to it?

Like all higher education institutions, at the LSA, we’ve been forced into distance learning. But the company of others is still key and will continue to be so. I’m for the mix of methods, combining computer working with sketching and model building, even filmmaking. Flexibility is the key. Almost any creative process can inform architecture. Surprise might also add value. I advocate disrupting the assumptions about how you learn. In the past, I’ve introduced projects that required designing and wearing a garment, or writing and then acting out a play, or making a design object and then filming it. We could add building an app, modelling wellbeing with AR, designing funky vehicles, or a straightforward table and chair. By adding any of these exercises, students can better engage with social evolution and avoid designing in a tick-box process. More than ever, students need to reach into other domains and broaden their mindsets.

© Nigel Coates, Coates Apartment, Glendower Place, London, 2016

© Nigel Coates, 2020

Content Curation and Interview by Annie Markitanis, Director of MDFF Greece & Cyprus, Partner of the Milano Design Film Festival